|

WELL LOGGING BASICS

WELL LOGGING BASICS

Well logging is the process of recording various physical, chemical,

electrical, or other properties of the rock/fluid mixtures penetrated

by drilling a borehole into the earth's cruste. A log is a record

of a voyage, similar to a ship's log or a travelog. In this case, the ship is

a measuring instrument of some kind, and the trip is taken into

and out of the wellbore.

In

its most usual form, an oil well log is a record displayed on

a graph with the measured physical property of the rock on one

axis and depth (distance from a near-surface reference) on the other axis.

More than one property may be displayed on the same graph.

Well

logs are recorded in nearly all oil and gas wells and in many

mineral and geothermal exploration and development wells. Although

useful in evaluating water wells, few are run for this purpose.

It was hot and breezy in California in 1932

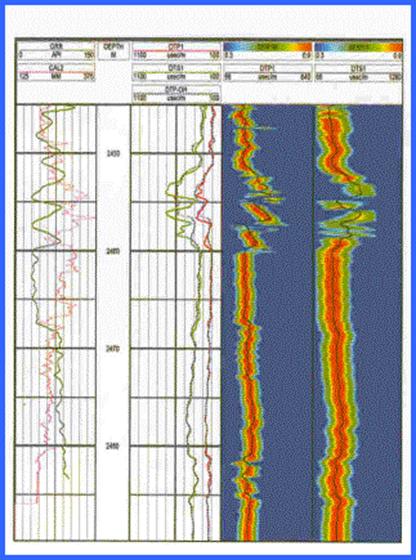

The traditional well log is a record of various measurements of

the physical properties of rocks recorded versus depth (left side of

illustration). Each wiggly line is a log curve, representing a

particular roc property. More recently, imaging logs have appeared

in which colour and position versus depth are used to display data

in more intuitive formats (right half of illustration).

None

of the logs actually measure the physical properties that are

of most interest to us, such as how much oil or gas is in the

ground, or how much is being produced. Such important knowledge

can only be derived, from the measured properties listed in the

box on the left

(and others), using a number of assumptions which, if true, will

give reasonable estimates of hydrocarbon or mineral resources. None

of the logs actually measure the physical properties that are

of most interest to us, such as how much oil or gas is in the

ground, or how much is being produced. Such important knowledge

can only be derived, from the measured properties listed in the

box on the left

(and others), using a number of assumptions which, if true, will

give reasonable estimates of hydrocarbon or mineral resources.

Thus,

analysis of log and related laboratory data is required. The art and science of log analysis

is mainly directed at reducing a large volume of data to more

manageable results, and reducing the possible error in the assumptions

and in the results based on them. When log analysis is combined

with other physical measurements on the rocks, such as core analysis

or petrographic data, the work is called petrophysics or petrophysical

analysis. The results of the analysis are called petrophysical

properties or mappable reservoir properties. The petrophysical

analysis is said to be “calibrated” when the porosity,

fluid saturation, and permeability results compare favourably

with core analysis data. Further confirmation of petrophysical

properties is obtained by production tests of the reservoir intervals.

The

use of well logs for evaluating mineral deposits other than oil

and gas, such as coal, potash, uranium, and hard rock sequences

has been practiced since the early 1930’s and is widespread

today. Although the vast majority of logs are run to evaluate

oil and gas wells, an increased number are being run for

other purposes, including evaluation of geothermal energy and

ground water. A large portion of this Handbook

TYPES OF LOGS

TYPES OF LOGS

Logs run on wireline into a hole which has just been drilled, and before it

is cased, are called open-hole logs. Logs run after the well is

cased are called cased-hole logs. Open hole logs are mainly used

to determine the petrophysical properties of the rocks. Some cased

hole logs are used for the same purpose. Others are used to assess

the integrity of the well completion; others are used to assess

fluid flow into the well.

Logs often make several measurements simultaneously and several

logging tools can be connected together to operate as a single

string of tools. The combinations have gained there own cryptic

names.

The terminology stems from how many individual

physical logging tools could be assembled and run in one pass into

the wellbore. As tools got smaller, you could fit more of them in

the derrick – took a lot of re-engineering to get all the signals to

pass thru all the tools. The terms "triple-combo" and "quad-combo"

are used to describe two specific tool string combinations in common

use today:

Triple-combo = resistivity + density + neutron

tools.

Quad-combo = resistivity + sonic + density +

neutron tools.

The gamma ray log is always included but doesn’t add to the tool

count.

A standard triple-combo is resistivity curves (with GR or SP or

both) plus density – neutron curves (with GR, caliper, density

correction, and PEF. Density + neutron counts as 2 of the 3 tools.

A

quad-combo adds a sonic log to the above tool string. This may

include only compressional sonic or both compressional plus shear

sonic. There may be more than one GR and caliper depending on the

era of the logs.

Some

combos can have spectral GR, which adds potassium, thorium, and

uranium curves.

Other

types of logs require no cable, such as a mud log which may record

up to 5 or 10 properties of the drilling fluid, or a drilling

log which records the rate of penetration and other functions

of the drilling process.

The

geology log, often called the stratigraphic log, strat log, or

sample description log, is a record of the rock samples retrieved

from the drilling mud, and is one of the primary sources of rock

and fluid descriptions for the well. It consists of a verbal description

of the rock type as well as qualitative or interpretive data concerning

evidence of the fluid content of the rock. These are all useful

logs and are used in any analysis of a well, if they are available.

Most

logs can now be recorded while drilling is going on or while

tripping the drill pipe. This is called

measurements while drilling (MWD) or logging while drilling (LWD).

Open-hole logs require that the drill string be removed from the

well bore before the logging tools can be lowered into the hole.

MWD does not have this need, so measurements are available continuously

as drilling proceeds.

A

composite log is made up of measurements and interpretations from

many sources of data. It is usually made up in the office in a

standard format (for the company or agency who owns the well).

Since it compresses a great deal of data onto one log, it is often

one of the most used items in the well file.

Most

open and cased-hole logs are recorded continuously as the tools

are pulled out of the hole. A few logs, however, may only be recorded

when the tool is stationary in the hole, such as the gravity meter

survey. Such logs are called station-by-station logs as opposed

to continuous logs. Some early station-by-station logs, by virtue

of significant improvements in measuring and recording techniques,

have become continuous logs. The first electrical log run in 1927

was station-by-station, but soon after, electrical logs were run

as continuous logs.

Most open hole logs are run in a conductive mud system. Muds

with relatively high resistivity are called fresh muds, and

those with low resistivity are called salt muds. Salt muds may

be salted on purpose to reduce erosion in shales or solution of

salt beds while drilling through them.

Oil-base muds are non-conductive and cause a few

problems, but not many are serious. You cannot run SP, microlog,

microlaterolog, or laterlog because they need conductive mud.

Dipmeter and Formation Micro Scanners need scratcher pads but

otherwise operate normally. Sonic, density, neutron, gamma ray,

NMR, caliper, induction logs all work normally.

Logs are used for a variety of purposes depending on the nature

of the data gathered. Correlation from well to well is the oldest

and probably the most common use of logs. It allows the subsurface

geologist to map formation depths and thicknesses and then to

identify conditions that could trap hydrocarbons.

Correlation

is usually based on the shapes of the recorded curves versus depth.

Correlation in complex geologic areas may be difficult or impossible,

and in any event requires corroboration from actual rock samples

for the initial correlations in an area. After the curve shape

patterns are recognized, they can often be used in subsequent

wells without relying too heavily on rock sample data. Correlation

is usually based on the shapes of the recorded curves versus depth.

Correlation in complex geologic areas may be difficult or impossible,

and in any event requires corroboration from actual rock samples

for the initial correlations in an area. After the curve shape

patterns are recognized, they can often be used in subsequent

wells without relying too heavily on rock sample data.

Identification

of the lithology of the rock sequence is another important use

of logs. A log shows many variations from top to bottom. Each

wiggle has significance, but it can be related to the rocks being

logged only by comparing the log with actual rock samples or a

core from the well. After acquiring experience in an area it is

possible for a log analyst to make an educated guess as to lithology

by looking at the log. Modern analytical methods permit more accurate

lithology identification, but this requires charts or mathematical

solutions in addition to the curve shapes.

One

of the important uses of logs today is the determination of rock

porosity. This measurement is significant because it tells how

much storage space a rock has for fluids. No log actually measures

porosity directly, but many analytical methods are available to

help estimate this important property.

Another

of the routine uses of logs is the determination of the water,

oil, or gas saturation in the rock pores. When the porosity, oil

or gas saturation, the thickness and extent of the reservoir are

known, then it is possible to tell how much hydrocarbon is in

place in the reservoir. Again, no log actually measures the fluid

saturation directly, so analysis of indirect measurements is required.

The logs most often run for the above purposes are resistivity,

sonic travel time, density, neutron, gamma ray and spontaneous

potential logs. Another

of the routine uses of logs is the determination of the water,

oil, or gas saturation in the rock pores. When the porosity, oil

or gas saturation, the thickness and extent of the reservoir are

known, then it is possible to tell how much hydrocarbon is in

place in the reservoir. Again, no log actually measures the fluid

saturation directly, so analysis of indirect measurements is required.

The logs most often run for the above purposes are resistivity,

sonic travel time, density, neutron, gamma ray and spontaneous

potential logs.

One

of the older, but very useful, surveys is the caliper log. In

open hole logging, it is used to determine hole volume and aids

the engineer in designing a cementing program. It also indicates

mud cake build-up and hole wash-out. Both of these indications

are of interest to the log analyst when he considers the other

logs. In cased hole work the caliper is often used to find casing

damage and separated casing.

A

more recent development in logging is fracture-finding. It is

important because fractures will often produce large quantities

of fluid even though the rock the fractures are in would not otherwise

produce commercially. Many open-hole logs have some artifacts

caused by fractures, but the formation micro-scanner and borehole

televiewer are the most useful.

When

it is time to perforate the casing to allow fluid to flow into

the well, there may be some doubt about how well the perforator

depths match the log depths. To overcome this uncertainty, a casing

collar gamma ray log is often run. This log is correlated to the

open-hole log. Even though the actual depths may not agree, the

zone of interest on the open hole logs is related to the collar

log depth. Then the perforating gun is positioned in relation

to the collars in the casing and perforating accuracy is assured. When

it is time to perforate the casing to allow fluid to flow into

the well, there may be some doubt about how well the perforator

depths match the log depths. To overcome this uncertainty, a casing

collar gamma ray log is often run. This log is correlated to the

open-hole log. Even though the actual depths may not agree, the

zone of interest on the open hole logs is related to the collar

log depth. Then the perforating gun is positioned in relation

to the collars in the casing and perforating accuracy is assured.

The

measurement of fluid flow in and near the wellbore is often of

vital importance. Such measurements can indicate channels behind

casing, casing leaks, packer leaks, tubing leaks, water influx

problems, cross flow from one reservoir to another, and other

production problems.

Another

common use for this type of measurement is the determination of

water input profiles in water injection wells. A thief zone may

take most of the water and leave the rest of the reservoir unflooded.

Surveys of this type point out the type of remedial action that

is necessary to establish a more desirable water input distribution.

Generally

it is not advisable to complete a well in a zone that has poor

bond between cement and casing without first squeezing in more

cement to seal the casing to the rock formation. A cement bond

or cement evaluation log is used to identify this problem.

The

temperature log is commonly used to indicate the top of cement

behind a newly cemented string of casing. The setting cement liberates

heat and warms up the well bore, which is thus recognizable on

a temperature log of the well.

Another

use for the temperature log is the location of points of fluid

entry in a well bore or of fluid flow behind casing. As the fluid

enters the well it expands and cools creating abnormally low temperature

in the well at the point of entry. Acoustic noise logs also find

flow entry and flow behind pipe by the noise caused by the flowing

fluid.

The

most significant change in the use of logs, in recent years, is

production monitoring. The thermal decay time log (often called

a pulsed neutron log) allows for the interpretation of porosity

and fluid saturation behind casing. The fluid saturation will

change over time as a reservoir is depleted by production, and

the changes may be monitored by logging at regular intervals,

say once a year. If the production pattern is not as predicted,

remedial action may be possible. The log is also used to provide

porosity and fluid saturation data in wells which are not, or

could not, be logged in the more conventional open-hole manner.

A

large suite of logging instruments is available to evaluate fluid

type, fluid flow, and mechanical conditions in producing or injecting

wells, in addition to those already mentioned. These are generically

called production logs and are usually run in cased holes, but

some are also effective in open hole or "bare-foot"

completions. Production log analysis is not described in this

book as excellent treatments are available elsewhere.

The

same logs that are used to evaluate porosity and water saturation

in oil and gas wells are also used to evaluate other resources

such as ground water, coal, potash, salt, uranium, oil shale,

gypsum, sulfur, geothermal energy, tar sands, and hard rock minerals.

Logs are also used to explore the earth's surface in general,

such as in the Deep Sea Drilling Program which has helped to document

the theory of plate tectonics, sea floor spreading, and continental

drift.

LOG SCALES and LAYOUT

LOG SCALES and LAYOUT

Logs

can be run on a number of vertical (depth) scales and quite a

variety of horizontal (curve value) scales.

Common

Logging Scales

| |

English |

Metric |

|

Often

Called |

Terminology |

Terminology |

|

Detail

scale or |

|

|

|

large

scale |

5"

= 100 ft |

1:240 1:200 is also very common |

|

Correlation

scale or |

2"

= 100 ft |

1:600

1:500 is also very common |

|

small

scale |

1"

= 100 ft |

1:1200

1:1000 is also very common |

|

Super

detail scale |

10"

= 100 ft |

1:120

1:100 is also very common |

|

* |

25"

= 100 ft |

1:48

1:50 is also very common |

|

Dipmeter

scale |

60"

= 100 ft |

1:20 |

| |

|

Correlation and Detail Scale Logs

The

spacing between depth grid lines is 10 feet or 5 meters for correlation

scales and 2 feet or 1 meter for other scales. Heavier grid lines

appear every 10 feet (5 meters) and every 50 feet (25 meters).

(Meters)

Metric and English (USA) Log Grids – Detail

Scale

Logs

are presented in the field in a three track presentation. The

pair of tracks 2 and 3 is often called track 4, which is used

to record curves with a large range in values.

Four

(or more) track presentations (with all tracks to the right hand

side of the depth numbers) is created in the course of computer

processed log analysis. These can be generated in the computer

on the logging truck or in the office. Some logs recorded prior

to 1946 have only two tracks, and logs run for special purposes

(eg. potash) have three tracks all to the right of the depth numbers.

Various Log Grid Styles

The

space where the depth numbers are printed is called the depth

track and is often used for annotation of tops, DST and core data

by the analyst. Both right and left hand margins can also be used

for annotation.

Note

that logarithmic scales can also vary in presentation. The standard

scale is 4 decades wide starting at 0.2 and going to 2000. This

can be shifted one decade to give a 2 to 20000 scale or a partial

decade to give 0.1 to 1000 or 0.3 to 3000.

Linear

scales can be ANY RANGE. So check every time to find out what

scale is current on the section of log you are analyzing.

Back-up

scales are shown on the log heading underneath the primary scale.

Back-up scales take over when the primary curve goes off-scale.

Back-ups can be the same sensitivity (ie. 140 to 240 is the back-up

scale to 40 to 140) or a multiple of the primary scale (ie. 0

to 500 is the back-up to a 0 to 50 scale). Usually, but not always,

the multiple is 10 to 1 and the first one tenth of the back-up

scale is blanked out to prevent a confusion of curve. Logs exist

with back-ups with multiples of 5, 10, 100 and 1000 (all could

be on the same log) which gives a considerable range of answers

if the wrong scale is selected by the analyst.

Primary, Backup, and Amplified Log Curves

The

use of logarithmic scales has reduced the need for back-up scales

on resistivity logs, but a back-up may also be seen to augment

a logarithmic scale. It will add another four decades to the scale

range. Back-ups are still common on other linear scales such as

the sonic, density, neutron and gamma-ray logs.

Amplified

scales are often presented on resistivity or sonic logs. For resistivity

logs the short normal curve can be shown amplified on a 0 to 2

or 0 to 4 scale, while the primary scale stays at 0 to 20 or 0

to 50 scale. The sonic log may show an amplified scale of 40 to

80 or 40 to 100 scale while the primary scale is 40 to 140. Amplified

scales are not used on logarithmic presentations, or on metric

sonic logs (scales of 100 to 300 or 100 to 500 usually give sufficient

detail with back-ups).

There are many variations in the presentation of well logs. There

are a few standard conventions, but local need often creates its

own conventions.

Usually

a log will be composed of several separate pieces spliced together

(splice can be physical, as separate pieces of film taped together,

or virtual as created by a computer playback): Usually

a log will be composed of several separate pieces spliced together

(splice can be physical, as separate pieces of film taped together,

or virtual as created by a computer playback):

Each

piece of log is recorded on film and the pieces are spliced together

in the order described above. A heading, with

basic well data, is spliced to the top of the correlation scale

film and a scale insert is spliced (usually) between each separate

piece of film. These inserts show the scale of each of the recorded

curves below the insert (and often above the insert as well).

On computerized logging units, the inserts may be an integral

part of the film.

The Parts of a Log

|